Coffin varnish, jiggle soup, and bathtub gin are just some of the colorful names used to describe the moonshine that filled Coastside stills and speakeasies during the Prohibition years of 1920 to 1933.

Thanks to a landscape of secluded canyons and fog-shrouded coves—plus close proximity to a major market such as San Francisco—bootlegging, moonshining, and speakeasies flourished along the Coastside during America’s noble experiment. Farmers hid cases of illegal hooch beneath their vegetables, rum-runners made midnight dashes to shore, clandestine stills churned in hidden canyons, and bootleg liquor flowed at local roadhouses. For thirteen years, Brussels sprouts took a backseat to booze during one of the juiciest chapters of Coastside history.

Bootleggers

In 1919 and 1920, Congress passed a series of amendments that prohibited alcohol, beginning with the Eighteenth Amendment which made the production, transport, and sale of alcohol illegal. The subsequent Volstead Act specified how the amendment would be enforced and defined what intoxicating beverages were to be outlawed.

Suddenly, the once quiet Coastside was teeming with bootleggers who were lured by its secluded shores, limited law enforcement, and close proximity to lucrative San Francisco speakeasies. The drink of choice was Canadian whisky—its distinct spelling distinguished from American whiskey—smuggled down to quiet Coastside waters and anchored twelve miles offshore, the limit of U.S. jurisdiction. Many ships listed their final port of call in Mexico because the U.S. Coast Guard would not board foreign-bound vessels unless a crime was witnessed.

There were numerous ways to get the forbidden cargo ashore. Armed with flashlights and a book of secret codes, beachbound co-conspirators would signal when the coast was clear for a skiff to come ashore. Sometimes, smugglers buried their illicit loot in the sand, but risked it being dug up by stealthy townsfolk. Ranchers would be coerced—with dollars and violence—to make their coastal land available to smugglers, and local men and boys were often recruited to help drag cases across the sand via sleds. When the Ocean Shore Railroad failed to bring promised tourism to the Coastside, residents were eager for another way to make a buck.

Federal prohibition agents, or “prohis”, and local police were charged with enforcing prohibition laws, but were often paid to turn a blind eye. “San Mateo County had a reputation for being a very wet county,” says Carmen Blair, Deputy Director of the San Mateo County Historical Association. “In the 1930s, Hillsborough mobster Sam Termini famously called it the most corrupt county in the state.”

Yet, smugglers weren’t immune to busts. Newspapers of the time were filled with prohibition-related shootouts worthy of a Humphrey Bogart flick. In 1923, Año Nuevo Island was the site of a violent clash between smugglers and the shotgun-wielding field agents who proved victorious.

Moonshiners

Illegal hooch didn’t always arrive via sea. The Eighteenth Amendment allowed for the consumption of alcohol at home, and, when it was ratified in 1919, residents had one year to stock up on alcohol before the law went into effect. Wealthy residents who crammed their cellars full of expensive wine and liquor didn’t go unnoticed by intrepid thieves.

Yet, much alcohol during this time was obtained the old-fashioned way: produced at home. Home stills flourished due in part to Italian immigrants who saw little reason to give up making grappa, and enterprising newcomers who readily purchased necessary equipment from newspaper adverts. Coastsiders who didn’t maintain a still of their own might get in on the action indirectly by selling gasoline and sugar to fuel a neighborhood moonshine operation.

Speakeasies

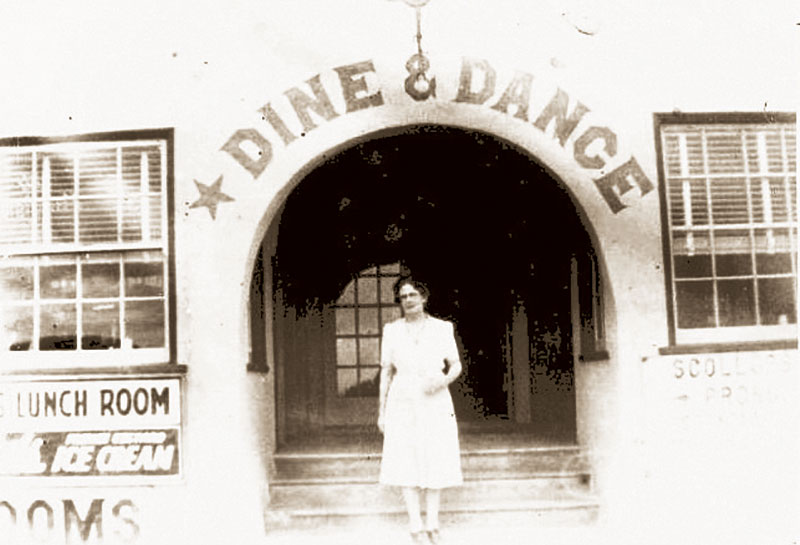

The current craft cocktail renaissance has revived the lingo and romanticized allure of the speakeasy, that clandestine watering hole also referred to as a blind tiger or blind pig. During Prohibition, San Francisco offered the best market for illegal booze. Trucks and autos outfitted with load-bearing springs would shuttle heavy cases over San Pedro Mountain to the city’s many speakeasies. Yet, some liquor stayed in town. Today, the Miramar Beach Restaurant welcomes diners with steaks and sunset vistas, but back in the 20s, it lured a more salacious crowd. The Ocean Beach Tavern, as it was known at the time, was designed as a prohibition roadhouse with revolving kitchen cabinets to conceal alcohol. Swigging bootleg liquor wasn’t the only shenanigans thought to have transpired. Current owner Mark Jamplis suspects it housed a second-floor bordello given the ten snug rooms—each big enough for a bed and a sink—that he discovered when he acquired the property.

Another popular Coastside haunt was Frank’s Place, now the Moss Beach Distillery, whose regulars included mystery writer Dashiell Hammett. In his short story, “The Girl with the Silver Eyes,” Hammett fictionalized Frank’s Place, noting that it was a relay station for smuggled booze, and that half of the intoxicating contraband arriving via the Pacific Ocean was unloaded in Half Moon Bay. Owner Frank Torres built his roadhouse in 1927 on coastal bluffs overlooking a secluded cove, the perfect locale for landing illegal whisky. Frank’s Place quickly became a swinging hangout for politicians and Hollywood celebs, and as such, was never raided.

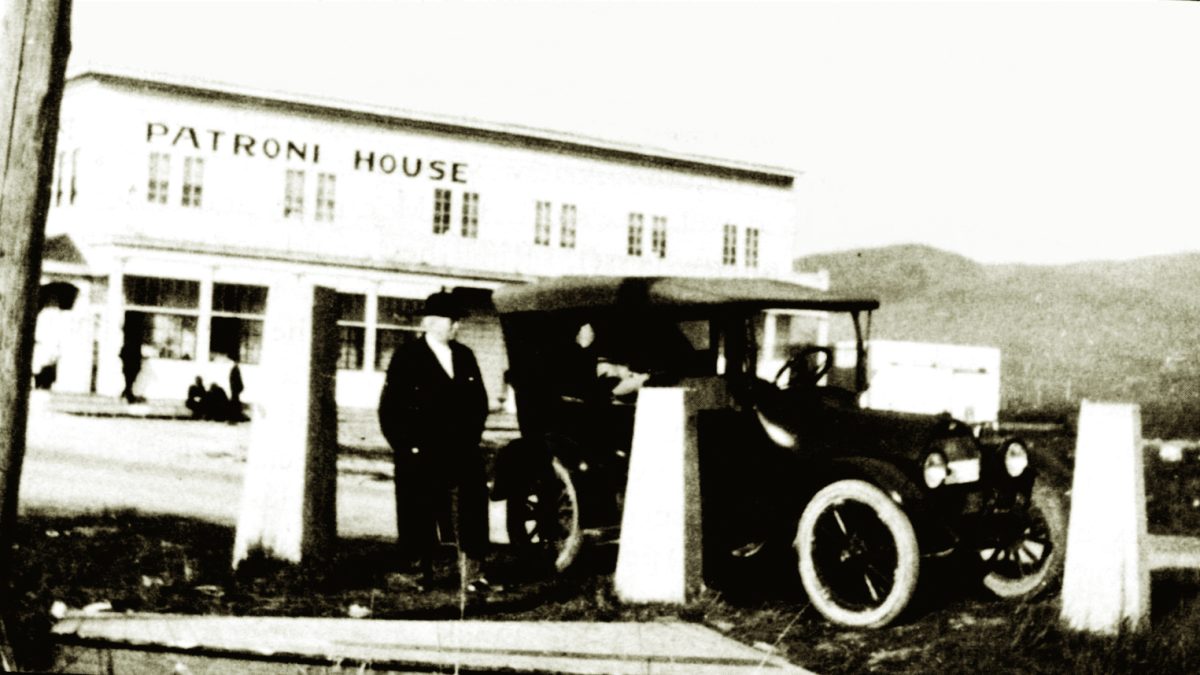

The same can’t be said for The Patroni House which attracted law enforcement on more than one occasion. Stocky John Patroni was known around town as “The Padrone,” and owned a two-story roadhouse that stood near the present site of the Half Moon Bay Brewing Company, adjacent to what is now Pillar Point Harbor. The cove’s breakwater had yet to be built, and Patroni maintained his own pier where he welcomed rum-runners to unload their whisky under the cover of darkness. A portion of that pier was later lost during an explosive confrontation between bootleggers and the Coast Guard.

Repeal

Disregard of prohibition laws wasn’t limited to shadowy figures and connected politicos. Drinking was seen as a part of daily life, and flaunting the law was widespread. One Montara resident noted that even his church maintained an illegal still. On December 5, 1933, the Twenty-first Amendment repealed the Eighteenth Amendment, ending prohibition, and putting the rum-runners and bootleggers out of business.

Today, visitors can relive the era by sipping a perfectly legal drink, and marveling at sepia photographs of the time at former speakeasies such as the Moss Beach Distillery and Miramar Beach Restaurant. You’ll also still find spirits being produced along the Coastside, but they’ve come a long way from the bathtub gin of the 20s. Pop into the Half Moon Bay Distillery where you can sample artisanal, small-batch spirits including an exceptionally smooth, locally produced vodka and gin. No password required.